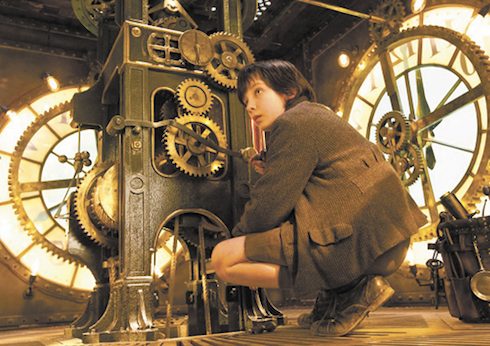

Martin Scorsese’s new film Hugo is a delight, mostly because it transcends its contemporaries—that is, other children’s movies—in looks and smarts. It helps that it’s an adaptation of Brian Selznick’s novel/picture book/graphic novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret, the 2008 Caldecott Medal winner for its innovative style and well-researched historical fiction. The movie is equally comfortable in its own skin of 1930s Paris; the screenwriters didn’t feel the need to throw in anachronisms or hip pop-culture references to draw in prepubescent audiences. The story is simply that of an orphan who winds up the clocks in the Paris train station and seeks to fix a machine his father left behind. Simple, but emotionally complex.

Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield, who you’ll soon see in Ender’s Game) is a different kind of street urchin than we’re used to seeing. Before he became a grubby thief hiding out behind clocks, he was a respectable child with an attentive clockmaker father. After his father dies, he has no choice but to escape to the train station and evade the orphan-hunting station inspector. That Hugo has fallen from grace is clear in his costume: A schoolboy uniform that he’s worn to pieces. Unfortunately, he’s helped himself with this fall by stealing food and parts from the station’s other vendors; consequently, the adults around him turn a blind eye to his suffering out of spite.

Luckily, he finds an ally in Isabelle (Kick-Ass‘ Chloe Moretz), a fellow orphan, but one who lives with her godparents and feels stifled. She’s excited by Hugo’s ragamuffin life and wants a real adventure. When she helps him to repair his father’s automaton—a wind-up mechanical man that can write a message—they stumble onto a mystery that spans the technology of the time, from clocks to the nascent art of moviemaking.

There’s something about clocks that enraptures us as readers and viewers; the metaphor of cogs that have gears to fit into, of a handmade trade that will one day be obsolete, speaks to growing up and struggling to discover one’s specific place and purpose in the world. Hugo’s story is filled with the same tragedy and intricacy as Watchmen‘s Jon Osterman before he became Dr. Manhattan.

Hugo doesn’t fall into the trap of ’00s children movie’s that condescend to their audiences and make the adults into bumbling idiots. Yes, Hugo and Isabelle are precocious, but in this story adults and children are equally complex.

To that end, there’s a great supporting cast: Sacha Baron Cohen is the unforgiving station agent who is himself part-machine thanks to a war wound; Emily Mortimer the flower girl he longs for; Ben Kingsley the enigmatic toymaker Papa Georges. And Harry Potter fans should keep their eyes peeled for small roles from the actresses who played Madame Maxime and Narcissa Malfoy.

Some of the details are childish—Hugo’s father is killed by the neutral, amorphous force of fire, rather than by the robbers you might assume would break into a museum—but the movie balances these with sly asides between the adults. Even though Asa Butterfield will capture your attention in most scenes, keep an ear out for the background dialogue to catch more grown-up jokes.

By chance, I ended up seeing the movie in 3-D, and I’m glad I did. The filmmakers really utilize the 3-D technology to set the atmosphere, from the first dizzying journey through the train station’s clocks to the Parisian winter outside with snowflakes hovering so close it seems like they’ll melt on your cheeks.

The one downside to the movie is the hitches in the plot brought about by frustrating omissions of information. Hugo could easily explain why he needs to steal parts to fix his father’s automaton, but because he doesn’t, he’s considered a good-for-nothing instead of the intelligent, passionate boy he actually is. However, this could have been intended as a character detail; it certainly keeps the plot chugging steadily along like a commuter train.

The stunning setting and effects, combined with the real-life cinema lore, will have you leaving the theater feeling like you actually learned something.

Natalie Zutter is a playwright, foodie, and the co-creator of Leftovers, a webcomic about food trucks in the zombie apocalypse. She’s currently the Associate Editor at Crushable, where she discusses movies, celebrity culture, and internet memes. You can find her on Twitter.